The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Works Of Balzac, by Honore de Balzac

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

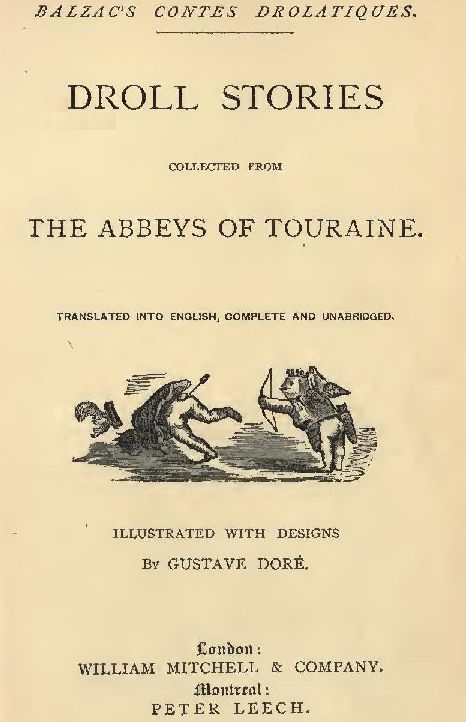

Title: The Works Of Balzac

A linked index to all Project Gutenberg editions

Author: Honore de Balzac

Editor: David Widger

Release Date: March 8, 2010 [EBook #31565]

Last Updated: February 3, 2019

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WORKS OF BALZAC ***

Produced by David Widger

Note: This work is dedicated to Dagny, who, 10 years ago, was part of the "Balzac Team" which produced 100 eBooks for Project Gutenberg.

DW

SCENES FROM PRIVATE LIFE

| At the Sign of the Cat and Racket

(La Maison du Chat-qui Pelote) The Ball at Sceaux (Le Bal de Sceaux) The Purse (La Bourse) Vendetta (La Vendetta) Madame Firmiani (Mme. Firmiani) A Second Home (Une Double Famille) Domestic Peace (La Paix du Menage) Paz (La Fausse Maitresse) Study of a Woman (Etude de femme) Another Study of Woman (Autre etude de femme) The Grand Breteche (La Grande Breteche) Albert Savarus (Albert Savarus) Letters of Two Brides (Memoires de deux Jeunes Mariees) A Daughter of Eve (Une Fille d'Eve) A Woman of Thirty (La Femme de Trente Ans) The Deserted Woman (La Femme abandonnee) La Grenadiere (La Grenadiere) The Message (Le Message) Gobseck (Gobseck) The Marriage Contract (Le Contrat de Mariage) A Start in Life (Un Debut dans la vie) Modeste Mignon (Modeste Mignon) Beatrix (Beatrix) Honorine (Honorine) Colonel Chabert (Le Colonel Chabert) The Atheist's Mass (La Messe de l'Athee) The Commission in Lunacy (L'Interdiction) Pierre Grassou (Pierre Grassou) |

SCENES FROM PROVINCIAL LIFE

| Ursule Mirouet (Ursule Mirouet) Eugenie Grandet (Eugenie Grandet) Pierrette (Les Celibataires, Pierrette) The Vicar of Tours (Le Cure de Tours) The Two Brothers, (The Black Sheep) (Un Menage de Garcon, La Rabouilleuse) The Illustrious Gaudissart (L'illustre Gaudissart, Parisians in the Country) The Muse of the Department (La Muse du departement) The Old Maid, Jealousies of a Country Town (La Vieille Fille, Les Rivalites) The Collection of Antiquities (Le Cabinet des antiques) The Lily of the Valley (Le Lys dans la Vallee) Two Poets, Lost Illusions:—I. (Les Deux Poetes, Illusions Perdues:—I.) A Distinguished Provincial at Paris (Un Grand homme de province a Paris, 1re partie) Eve and David (Eve et David) |

SCENES FROM PARISIAN LIFE

| Scenes from a Courtesan's Life, Esther

Happy (Splendeurs et Miseres des Courtisanes What Love Costs an Old Man (A combien l'amour revient aux vieillards) The End of Evil Ways (Ou menent les mauvais Chemins) Vautrin's Last Avatar (La derniere Incarnation de Vautrin) A Prince of Bohemia (Un Prince de la Boheme) A Man of Business (Un Homme d'affaires) Gaudissart II (Gaudissart II.) Unconscious Comedians, The Unconscious Humorists (Les Comediens sans le savoir) Ferragus, The Thirteen (Ferragus, Histoire des Treize) The Duchesse de Langeais (La Duchesse de Langeais) Girl with the Golden Eyes (La Fille aux yeux d'or) Father Goriot, Old Goriot (Le Pere Goriot) Rise and Fall of Cesar Birotteau (Grandeur et Decadence de Cesar Birotteau) The Firm of Nucingen (La Maison Nucingen) Secrets of the Princesse de Cadignan (Les Secrets de la princesse de Cadignan) Bureaucracy, The Government Clerks (Les Employes) Sarrasine (Sarrasine) Facino Cane (Facino Cane) Cousin Betty, Poor Relations:—I. (La Cousine Bette, Les Parents Pauvres:—I.) Cousin Pons, Poor Relations:—II. (Le Cousin Pons, Les Parents Pauvres:—II.) The Lesser Bourgeoisie, The Middle Classes (Les Petits Bourgeois) |

SCENES FROM POLITICAL LIFE

| An Historical Mystery, The Gondreville

Mystery (Une Tenebreuse Affaire) An Episode Under the Terror (Un Episode sous la Terreur) Brotherhood of Consolation, Seamy Side of History (Mme. de la Chanterie, L'Envers de l'Histoire Contemporaine) Initiated, The Initiate (L'Initie) Z. Marcas (Z. Marcas) The Deputy of Arcis, The Member for Arcis (Le Depute d'Arcis) |

SCENES FROM MILITARY LIFE

| The Chouans (Les

Chouans) A Passion in the Desert (Une Passion dans le desert) |

SCENES FROM COUNTRY LIFE

| The Country Doctor (Le Medecin

de Campagne) The Village Rector, The Country Parson (Le Cure de Village) Sons of the Soil, The Peasantry (Les Paysans) |

PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES

| The Magic Skin (La Peau de

Chagrin) The Alkahest, The Quest of the Absolute (La Recherche de l'Absolu) Christ in Flanders (Jesus-Christ en Flandre) Melmoth Reconciled (Melmoth reconcilie) The Unknown Masterpiece, The Hidden Masterpiece (Le Chef-d'oeuvre inconnu) The Hated Son (L'Enfant Maudit) Gambara (Gambara) Massimilla Doni (Massimilla Doni) Juana, The Maranas (Les Marana) Farewell (Adieu) The Recruit, The Conscript (Le Requisitionnaire) El Verdugo (El Verdugo) A Drama on the Seashore, A Seaside Tragedy (Un Drame au bord de la mer) The Red Inn (L'Auberge rouge) The Elixir of Life (L'Elixir de longue vie) Maitre Cornelius (Maitre Cornelius) Catherine de' Medici, The Calvinist Martyr (Sur Catherine de Medicis, Le Martyr calviniste) The Ruggieri's Secret, (La Confidence des Ruggieri) The Two Dreams (Les Deux Reves) Louis Lambert (Louis Lambert) The Exiles (Les Proscrits) Seraphita (Seraphita) |

Honore de Balzac

(1799-1850)

A Street of Paris

(With many Paintings)

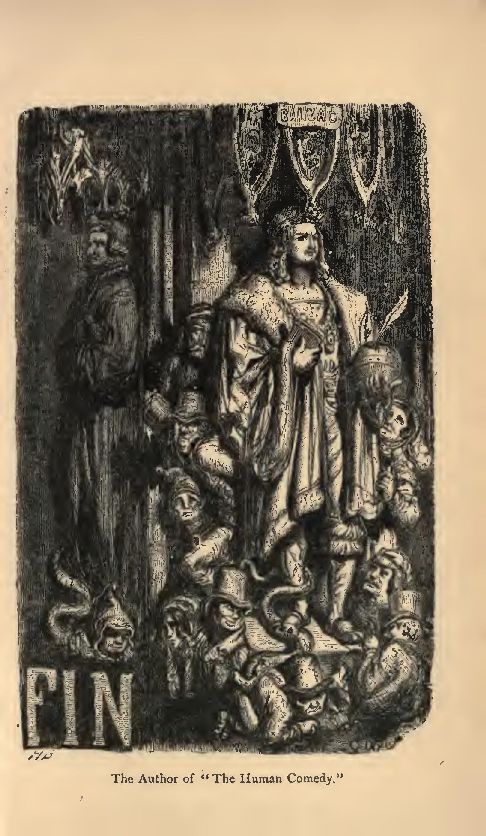

The Human Comedy

One Hundred Balzac Books and Stories Listed in Alphabetical

Order:

Preparer’s Note:

The Duchesse of Langeais is the second part of a trilogy. Part one is entitled Ferragus and part three is The Girl with the Golden Eyes. The three stories are frequently combined under the title The Thirteen.

In a Spanish city on an island in the Mediterranean, there stands a convent of the Order of Barefoot Carmelites, where the rule instituted by St. Theresa is still preserved with all the first rigor of the reformation brought about by that illustrious woman. Extraordinary as this may seem, it is none the less true. Almost every religious house in the Peninsula, or in Europe for that matter, was either destroyed or disorganized by the outbreak of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars; but as this island was protected through those times by the English fleet, its wealthy convent and peaceable inhabitants were secure from the general trouble and spoliation. The storms of many kinds which shook the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century spent their force before they reached those cliffs at so short a distance from the coast of Andalusia.

If the rumour of the Emperor’s name so much as reached the shore of the island, it is doubtful whether the holy women kneeling in the cloisters grasped the reality of his dream-like progress of glory, or the majesty that blazed in flame across kingdom after kingdom during his meteor life.

In the minds of the Roman Catholic world, the convent stood out pre-eminent for a stern discipline which nothing had changed; the purity of its rule had attracted unhappy women from the furthest parts of Europe, women deprived of all human ties, sighing after the long suicide accomplished in the breast of God. No convent, indeed, was so well fitted for that complete detachment of the soul from all earthly things, which is demanded by the religious life, albeit on the continent of Europe there are many convents magnificently adapted to the purpose of their existence. Buried away in the loneliest valleys, hanging in mid-air on the steepest mountainsides, set down on the brink of precipices, in every place man has sought for the poetry of the Infinite, the solemn awe of Silence; in every place man has striven to draw closer to God, seeking Him on mountain peaks, in the depths below the crags, at the cliff’s edge; and everywhere man has found God. But nowhere, save on this half-European, half-African ledge of rock could you find so many different harmonies, combining so to raise the soul, that the sharpest pain comes to be like other memories; the strongest impressions are dulled, till the sorrows of life are laid to rest in the depths.

The convent stands on the highest point of the crags at the uttermost end of the island. On the side towards the sea the rock was once rent sheer away in some globe-cataclysm; it rises up a straight wall from the base where the waves gnaw at the stone below high-water mark. Any assault is made impossible by the dangerous reefs that stretch far out to sea, with the sparkling waves of the Mediterranean playing over them. So, only from the sea can you discern the square mass of the convent built conformably to the minute rules laid down as to the shape, height, doors, and windows of monastic buildings. From the side of the town, the church completely hides the solid structure of the cloisters and their roofs, covered with broad slabs of stone impervious to sun or storm or gales of wind.

The church itself, built by the munificence of a Spanish family, is the crowning edifice of the town. Its fine, bold front gives an imposing and picturesque look to the little city in the sea. The sight of such a city, with its close-huddled roofs, arranged for the most part amphitheatre-wise above a picturesque harbour, and crowned by a glorious cathedral front with triple-arched Gothic doorways, belfry towers, and filigree spires, is a spectacle surely in every way the sublimest on earth. Religion towering above daily life, to put men continually in mind of the End and the way, is in truth a thoroughly Spanish conception. But now surround this picture by the Mediterranean, and a burning sky, imagine a few palms here and there, a few stunted evergreen trees mingling their waving leaves with the motionless flowers and foliage of carved stone; look out over the reef with its white fringes of foam in contrast to the sapphire sea; and then turn to the city, with its galleries and terraces whither the townsfolk come to take the air among their flowers of an evening, above the houses and the tops of the trees in their little gardens; add a few sails down in the harbour; and lastly, in the stillness of falling night, listen to the organ music, the chanting of the services, the wonderful sound of bells pealing out over the open sea. There is sound and silence everywhere; oftener still there is silence over all.

The church is divided within into a sombre mysterious nave and narrow aisles. For some reason, probably because the winds are so high, the architect was unable to build the flying buttresses and intervening chapels which adorn almost all cathedrals, nor are there openings of any kind in the walls which support the weight of the roof. Outside there is simply the heavy wall structure, a solid mass of grey stone further strengthened by huge piers placed at intervals. Inside, the nave and its little side galleries are lighted entirely by the great stained-glass rose-window suspended by a miracle of art above the centre doorway; for upon that side the exposure permits of the display of lacework in stone and of other beauties peculiar to the style improperly called Gothic.

The larger part of the nave and aisles was left for the townsfolk, who came and went and heard mass there. The choir was shut off from the rest of the church by a grating and thick folds of brown curtain, left slightly apart in the middle in such a way that nothing of the choir could be seen from the church except the high altar and the officiating priest. The grating itself was divided up by the pillars which supported the organ loft; and this part of the structure, with its carved wooden columns, completed the line of the arcading in the gallery carried by the shafts in the nave. If any inquisitive person, therefore, had been bold enough to climb upon the narrow balustrade in the gallery to look down into the choir, he could have seen nothing but the tall eight-sided windows of stained glass beyond the high altar.

At the time of the French expedition into Spain to establish Ferdinand VII once more on the throne, a French general came to the island after the taking of Cadiz, ostensibly to require the recognition of the King’s Government, really to see the convent and to find some means of entering it. The undertaking was certainly a delicate one; but a man of passionate temper, whose life had been, as it were, but one series of poems in action, a man who all his life long had lived romances instead of writing them, a man pre-eminently a Doer, was sure to be tempted by a deed which seemed to be impossible.

To open the doors of a convent of nuns by lawful means! The metropolitan or the Pope would scarcely have permitted it! And as for force or stratagem—might not any indiscretion cost him his position, his whole career as a soldier, and the end in view to boot? The Duc d’Angouleme was still in Spain; and of all the crimes which a man in favour with the Commander-in-Chief might commit, this one alone was certain to find him inexorable. The General had asked for the mission to gratify private motives of curiosity, though never was curiosity more hopeless. This final attempt was a matter of conscience. The Carmelite convent on the island was the only nunnery in Spain which had baffled his search.

As he crossed from the mainland, scarcely an hour’s distance, he felt a presentiment that his hopes were to be fulfilled; and afterwards, when as yet he had seen nothing of the convent but its walls, and of the nuns not so much as their robes; while he had merely heard the chanting of the service, there were dim auguries under the walls and in the sound of the voices to justify his frail hope. And, indeed, however faint those so unaccountable presentiments might be, never was human passion more vehemently excited than the General’s curiosity at that moment. There are no small events for the heart; the heart exaggerates everything; the heart weighs the fall of a fourteen-year-old Empire and the dropping of a woman’s glove in the same scales, and the glove is nearly always the heavier of the two. So here are the facts in all their prosaic simplicity. The facts first, the emotions will follow.

An hour after the General landed on the island, the royal authority was re-established there. Some few Constitutional Spaniards who had found their way thither after the fall of Cadiz were allowed to charter a vessel and sail for London. So there was neither resistance nor reaction. But the change of government could not be effected in the little town without a mass, at which the two divisions under the General’s command were obliged to be present. Now, it was upon this mass that the General had built his hopes of gaining some information as to the sisters in the convent; he was quite unaware how absolutely the Carmelites were cut off from the world; but he knew that there might be among them one whom he held dearer than life, dearer than honour.

His hopes were cruelly dashed at once. Mass, it is true, was celebrated in state. In honour of such a solemnity, the curtains which always hid the choir were drawn back to display its riches, its valuable paintings and shrines so bright with gems that they eclipsed the glories of the ex-votos of gold and silver hung up by sailors of the port on the columns in the nave. But all the nuns had taken refuge in the organ-loft. And yet, in spite of this first check, during this very mass of thanksgiving, the most intimately thrilling drama that ever set a man’s heart beating opened out widely before him.

The sister who played the organ aroused such intense enthusiasm, that not a single man regretted that he had come to the service. Even the men in the ranks were delighted, and the officers were in ecstasy. As for the General, he was seemingly calm and indifferent. The sensations stirred in him as the sister played one piece after another belong to the small number of things which it is not lawful to utter; words are powerless to express them; like death, God, eternity, they can only be realised through their one point of contact with humanity. Strangely enough, the organ music seemed to belong to the school of Rossini, the musician who brings most human passion into his art.

Some day his works, by their number and extent, will receive the reverence due to the Homer of music. From among all the scores that we owe to his great genius, the nun seemed to have chosen Moses in Egypt for special study, doubtless because the spirit of sacred music finds therein its supreme expression. Perhaps the soul of the great musician, so gloriously known to Europe, and the soul of this unknown executant had met in the intuitive apprehension of the same poetry. So at least thought two dilettanti officers who must have missed the Theatre Favart in Spain.

At last in the Te Deum no one could fail to discern a French soul in the sudden change that came over the music. Joy for the victory of the Most Christian King evidently stirred this nun’s heart to the depths. She was a Frenchwoman beyond mistake. Soon the love of country shone out, breaking forth like shafts of light from the fugue, as the sister introduced variations with all a Parisienne’s fastidious taste, and blended vague suggestions of our grandest national airs with her music. A Spaniard’s fingers would not have brought this warmth into a graceful tribute paid to the victorious arms of France. The musician’s nationality was revealed.

“We find France everywhere, it seems,” said one of the men.

The General had left the church during the Te Deum; he could not listen any longer. The nun’s music had been a revelation of a woman loved to frenzy; a woman so carefully hidden from the world’s eyes, so deeply buried in the bosom of the Church, that hitherto the most ingenious and persistent efforts made by men who brought great influence and unusual powers to bear upon the search had failed to find her. The suspicion aroused in the General’s heart became all but a certainty with the vague reminiscence of a sad, delicious melody, the air of Fleuve du Tage. The woman he loved had played the prelude to the ballad in a boudoir in Paris, how often! and now this nun had chosen the song to express an exile’s longing, amid the joy of those that triumphed. Terrible sensation! To hope for the resurrection of a lost love, to find her only to know that she was lost, to catch a mysterious glimpse of her after five years—five years, in which the pent-up passion, chafing in an empty life, had grown the mightier for every fruitless effort to satisfy it!

Who has not known, at least once in his life, what it is to lose some precious thing; and after hunting through his papers, ransacking his memory, and turning his house upside down; after one or two days spent in vain search, and hope, and despair; after a prodigious expenditure of the liveliest irritation of soul, who has not known the ineffable pleasure of finding that all-important nothing which had come to be a king of monomania? Very good. Now, spread that fury of search over five years; put a woman, put a heart, put love in the place of the trifle; transpose the monomania into the key of high passion; and, furthermore, let the seeker be a man of ardent temper, with a lion’s heart and a leonine head and mane, a man to inspire awe and fear in those who come in contact with him—realise this, and you may, perhaps, understand why the General walked abruptly out of the church when the first notes of a ballad, which he used to hear with a rapture of delight in a gilt-paneled boudoir, began to vibrate along the aisles of the church in the sea.

The General walked away down the steep street which led to the port, and only stopped when he could not hear the deep notes of the organ. Unable to think of anything but the love which broke out in volcanic eruption, filling his heart with fire, he only knew that the Te Deum was over when the Spanish congregation came pouring out of the church. Feeling that his behaviour and attitude might seem ridiculous, he went back to head the procession, telling the alcalde and the governor that, feeling suddenly faint, he had gone out into the air. Casting about for a plea for prolonging his stay, it at once occurred to him to make the most of this excuse, framed on the spur of the moment. He declined, on a plea of increasing indisposition, to preside at the banquet given by the town to the French officers, betook himself to his bed, and sent a message to the Major-General, to the effect that temporary illness obliged him to leave the Colonel in command of the troops for the time being. This commonplace but very plausible stratagem relieved him of all responsibility for the time necessary to carry out his plans. The General, nothing if not “catholic and monarchical,” took occasion to inform himself of the hours of the services, and manifested the greatest zeal for the performance of his religious duties, piety which caused no remark in Spain.

The very next day, while the division was marching out of the town, the General went to the convent to be present at vespers. He found an empty church. The townsfolk, devout though they were, had all gone down to the quay to watch the embarkation of the troops. He felt glad to be the only man there. He tramped noisily up the nave, clanking his spurs till the vaulted roof rang with the sound; he coughed, he talked aloud to himself to let the nuns know, and more particularly to let the organist know that if the troops were gone, one Frenchman was left behind. Was this singular warning heard and understood? He thought so. It seemed to him that in the Magnificat the organ made response which was borne to him on the vibrating air. The nun’s spirit found wings in music and fled towards him, throbbing with the rhythmical pulse of the sounds. Then, in all its might, the music burst forth and filled the church with warmth. The Song of Joy set apart in the sublime liturgy of Latin Christianity to express the exaltation of the soul in the presence of the glory of the ever-living God, became the utterance of a heart almost terrified by its gladness in the presence of the glory of a mortal love; a love that yet lived, a love that had risen to trouble her even beyond the grave in which the nun is laid, that she may rise again as the bride of Christ.

The organ is in truth the grandest, the most daring, the most magnificent of all instruments invented by human genius. It is a whole orchestra in itself. It can express anything in response to a skilled touch. Surely it is in some sort a pedestal on which the soul poises for a flight forth into space, essaying on her course to draw picture after picture in an endless series, to paint human life, to cross the Infinite that separates heaven from earth? And the longer a dreamer listens to those giant harmonies, the better he realizes that nothing save this hundred-voiced choir on earth can fill all the space between kneeling men, and a God hidden by the blinding light of the Sanctuary. The music is the one interpreter strong enough to bear up the prayers of humanity to heaven, prayer in its omnipotent moods, prayer tinged by the melancholy of many different natures, coloured by meditative ecstasy, upspringing with the impulse of repentance—blended with the myriad fancies of every creed. Yes. In those long vaulted aisles the melodies inspired by the sense of things divine are blended with a grandeur unknown before, are decked with new glory and might. Out of the dim daylight, and the deep silence broken by the chanting of the choir in response to the thunder of the organ, a veil is woven for God, and the brightness of His attributes shines through it.

And this wealth of holy things seemed to be flung down like a grain of incense upon the fragile altar raised to Love beneath the eternal throne of a jealous and avenging God. Indeed, in the joy of the nun there was little of that awe and gravity which should harmonize with the solemnities of the Magnificat. She had enriched the music with graceful variations, earthly gladness throbbing through the rhythm of each. In such brilliant quivering notes some great singer might strive to find a voice for her love, her melodies fluttered as a bird flutters about her mate. There were moments when she seemed to leap back into the past, to dally there now with laughter, now with tears. Her changing moods, as it were, ran riot. She was like a woman excited and happy over her lover’s return.

But at length, after the swaying fugues of delirium, after the marvellous rendering of a vision of the past, a revulsion swept over the soul that thus found utterance for itself. With a swift transition from the major to the minor, the organist told her hearer of her present lot. She gave the story of long melancholy broodings, of the slow course of her moral malady. How day by day she deadened the senses, how every night cut off one more thought, how her heart was slowly reduced to ashes. The sadness deepened shade after shade through languid modulations, and in a little while the echoes were pouring out a torrent of grief. Then on a sudden, high notes rang out like the voices of angels singing together, as if to tell the lost but not forgotten lover that their spirits now could only meet in heaven. Pathetic hope! Then followed the Amen. No more joy, no more tears in the air, no sadness, no regrets. The Amen was the return to God. The final chord was deep, solemn, even terrible; for the last rumblings of the bass sent a shiver through the audience that raised the hair on their heads; the nun shook out her veiling of crepe, and seemed to sink again into the grave from which she had risen for a moment. Slowly the reverberations died away; it seemed as if the church, but now so full of light, had returned to thick darkness.

The General had been caught up and borne swiftly away by this strong-winged spirit; he had followed the course of its flight from beginning to end. He understood to the fullest extent the imagery of that burning symphony; for him the chords reached deep and far. For him, as for the sister, the poem meant future, present, and past. Is not music, and even opera music, a sort of text, which a susceptible or poetic temper, or a sore and stricken heart, may expand as memories shall determine? If a musician must needs have the heart of a poet, must not the listener too be in a manner a poet and a lover to hear all that lies in great music? Religion, love, and music—what are they but a threefold expression of the same fact, of that craving for expansion which stirs in every noble soul. And these three forms of poetry ascend to God, in whom all passion on earth finds its end. Wherefore the holy human trinity finds a place amid the infinite glories of God; of God, whom we always represent surrounded with the fires of love and seistrons of gold—music and light and harmony. Is not He the Cause and the End of all our strivings?

The French General guessed rightly that here in the desert, on this bare rock in the sea, the nun had seized upon music as an outpouring of the passion that still consumed her. Was this her manner of offering up her love as a sacrifice to God? Or was it Love exultant in triumph over God? The questions were hard to answer. But one thing at least the General could not mistake—in this heart, dead to the world, the fire of passion burned as fiercely as in his own.

Vespers over, he went back to the alcalde with whom he was staying. In the all-absorbing joy which comes in such full measure when a satisfaction sought long and painfully is attained at last, he could see nothing beyond this—he was still loved! In her heart love had grown in loneliness, even as his love had grown stronger as he surmounted one barrier after another which this woman had set between them! The glow of soul came to its natural end. There followed a longing to see her again, to contend with God for her, to snatch her away—a rash scheme, which appealed to a daring nature. He went to bed, when the meal was over, to avoid questions; to be alone and think at his ease; and he lay absorbed by deep thought till day broke.

He rose only to go to mass. He went to the church and knelt close to the screen, with his forehead touching the curtain; he would have torn a hole in it if he had been alone, but his host had come with him out of politeness, and the least imprudence might compromise the whole future of his love, and ruin the new hopes.

The organ sounded, but it was another player, and not the nun of the last two days whose hands touched the keys. It was all colorless and cold for the General. Was the woman he loved prostrated by emotion which well-nigh overcame a strong man’s heart? Had she so fully realised and shared an unchanged, longed-for love, that now she lay dying on her bed in her cell? While innumerable thoughts of this kind perplexed his mind, the voice of the woman he worshipped rang out close beside him; he knew its clear resonant soprano. It was her voice, with that faint tremor in it which gave it all the charm that shyness and diffidence gives to a young girl; her voice, distinct from the mass of singing as a prima donna’s in the chorus of a finale. It was like a golden or silver thread in dark frieze.

It was she! There could be no mistake. Parisienne now as ever, she had not laid coquetry aside when she threw off worldly adornments for the veil and the Carmelite’s coarse serge. She who had affirmed her love last evening in the praise sent up to God, seemed now to say to her lover, “Yes, it is I. I am here. My love is unchanged, but I am beyond the reach of love. You will hear my voice, my soul shall enfold you, and I shall abide here under the brown shroud in the choir from which no power on earth can tear me. You shall never see me more!”

“It is she indeed!” the General said to himself, raising his head. He had leant his face on his hands, unable at first to bear the intolerable emotion that surged like a whirlpool in his heart, when that well-known voice vibrated under the arcading, with the sound of the sea for accompaniment.

Storm was without, and calm within the sanctuary. Still that rich voice poured out all its caressing notes; it fell like balm on the lover’s burning heart; it blossomed upon the air—the air that a man would fain breathe more deeply to receive the effluence of a soul breathed forth with love in the words of the prayer. The alcalde coming to join his guest found him in tears during the elevation, while the nun was singing, and brought him back to his house. Surprised to find so much piety in a French military man, the worthy magistrate invited the confessor of the convent to meet his guest. Never had news given the General more pleasure; he paid the ecclesiastic a good deal of attention at supper, and confirmed his Spanish hosts in the high opinion they had formed of his piety by a not wholly disinterested respect.

He inquired with gravity how many sisters there were in the convent, and asked for particulars of its endowment and revenues, as if from courtesy he wished to hear the good priest discourse on the subject most interesting to him. He informed himself as to the manner of life led by the holy women. Were they allowed to go out of the convent, or to see visitors?

“Senor,” replied the venerable churchman, “the rule is strict. A woman cannot enter a monastery of the order of St. Bruno without a special permission from His Holiness, and the rule here is equally stringent. No man may enter a convent of Barefoot Carmelites unless he is a priest specially attached to the services of the house by the Archbishop. None of the nuns may leave the convent; though the great Saint, St. Theresa, often left her cell. The Visitor or the Mothers Superior can alone give permission, subject to an authorization from the Archbishop, for a nun to see a visitor, and then especially in a case of illness. Now we are one of the principal houses, and consequently we have a Mother Superior here. Among other foreign sisters there is one Frenchwoman, Sister Theresa; she it is who directs the music in the chapel.”

“Oh!” said the General, with feigned surprise. “She must have rejoiced over the victory of the House of Bourbon.”

“I told them the reason of the mass; they are always a little bit inquisitive.”

“But Sister Theresa may have interests in France. Perhaps she would like to send some message or to hear news.”

“I do not think so. She would have come to ask me.”

“As a fellow-countryman, I should be quite curious to see her,” said the General. “If it is possible, if the Lady Superior consents, if——”

“Even at the grating and in the Reverend Mother’s presence, an interview would be quite impossible for anybody whatsoever; but, strict as the Mother is, for a deliverer of our holy religion and the throne of his Catholic Majesty, the rule might be relaxed for a moment,” said the confessor, bB469linking. “I will speak about it.”

“How old is Sister Theresa?” inquired the lover. He dared not ask any questions of the priest as to the nun’s beauty.

“She does not reckon years now,” the good man answered, with a simplicity that made the General shudder.

Next day before siesta, the confessor came to inform the French General that Sister Theresa and the Mother consented to receive him at the grating in the parlour before vespers. The General spent the siesta in pacing to and fro along the quay in the noonday heat. Thither the priest came to find him, and brought him to the convent by way of the gallery round the cemetery. Fountains, green trees, and rows of arcading maintained a cool freshness in keeping with the place.

At the further end of the long gallery the priest led the way into a large room divided in two by a grating covered with a brown curtain. In the first, and in some sort of public half of the apartment, where the confessor left the newcomer, a wooden bench ran round the wall, and two or three chairs, also of wood, were placed near the grating. The ceiling consisted of bare unornamented joists and cross-beams of ilex wood. As the two windows were both on the inner side of the grating, and the dark surface of the wood was a bad reflector, the light in the place was so dim that you could scarcely see the great black crucifix, the portrait of Saint Theresa, and a picture of the Madonna which adorned the grey parlour walls. Tumultuous as the General’s feelings were, they took something of the melancholy of the place. He grew calm in that homely quiet. A sense of something vast as the tomb took possession of him beneath the chill unceiled roof. Here, as in the grave, was there not eternal silence, deep peace—the sense of the Infinite? And besides this there was the quiet and the fixed thought of the cloister—a thought which you felt like a subtle presence in the air, and in the dim dusk of the room; an all-pervasive thought nowhere definitely expressed, and looming the larger in the imagination; for in the cloister the great saying, “Peace in the Lord,” enters the least religious soul as a living force.

The monk’s life is scarcely comprehensible. A man seems confessed a weakling in a monastery; he was born to act, to live out a life of work; he is evading a man’s destiny in his cell. But what man’s strength, blended with pathetic weakness, is implied by a woman’s choice of the convent life! A man may have any number of motives for burying himself in a monastery; for him it is the leap over the precipice. A woman has but one motive—she is a woman still; she betrothes herself to a Heavenly Bridegroom. Of the monk you may ask, “Why did you not fight your battle?” But if a woman immures herself in the cloister, is there not always a sublime battle fought first?

At length it seemed to the General that that still room, and the lonely convent in the sea, were full of thoughts of him. Love seldom attains to solemnity; yet surely a love still faithful in the breast of God was something solemn, something more than a man had a right to look for as things are in this nineteenth century? The infinite grandeur of the situation might well produce an effect upon the General’s mind; he had precisely enough elevation of soul to forget politics, honours, Spain, and society in Paris, and to rise to the height of this lofty climax. And what in truth could be more tragic? How much must pass in the souls of these two lovers, brought together in a place of strangers, on a ledge of granite in the sea; yet held apart by an intangible, unsurmountable barrier! Try to imagine the man saying within himself, “Shall I triumph over God in her heart?” when a faint rustling sound made him quiver, and the curtain was drawn aside.

Between him and the light stood a woman. Her face was hidden by the veil that drooped from the folds upon her head; she was dressed according to the rule of the order in a gown of the colour become proverbial. Her bare feet were hidden; if the General could have seen them, he would have known how appallingly thin she had grown; and yet in spite of the thick folds of her coarse gown, a mere covering and no ornament, he could guess how tears, and prayer, and passion, and loneliness had wasted the woman before him.

An ice-cold hand, belonging, no doubt, to the Mother Superior, held back the curtain. The General gave the enforced witness of their interview a searching glance, and met the dark, inscrutable gaze of an aged recluse. The Mother might have been a century old, but the bright, youthful eyes belied the wrinkles that furrowed her pale face.

“Mme la Duchesse,” he began, his voice shaken with emotion, “does your companion understand French?” The veiled figure bowed her head at the sound of his voice.

“There is no duchess here,” she replied. “It is Sister Theresa whom you see before you. She whom you call my companion is my mother in God, my superior here on earth.”

The words were so meekly spoken by the voice that sounded in other years amid harmonious surroundings of refined luxury, the voice of a queen of fashion in Paris. Such words from the lips that once spoke so lightly and flippantly struck the General dumb with amazement.

“The Holy Mother only speaks Latin and Spanish,” she added.

“I understand neither. Dear Antoinette, make my excuses to her.”

The light fell full upon the nun’s figure; a thrill of deep emotion betrayed itself in a faint quiver of her veil as she heard her name softly spoken by the man who had been so hard in the past.

“My brother,” she said, drawing her sleeve under her veil, perhaps to brush tears away, “I am Sister Theresa.”

Then, turning to the Superior, she spoke in Spanish; the General knew enough of the language to understand what she said perfectly well; possibly he could have spoken it had he chosen to do so.

“Dear Mother, the gentleman presents his respects to you, and begs you to pardon him if he cannot pay them himself, but he knows neither of the languages which you speak——”

The aged nun bent her head slowly, with an expression of angelic sweetness, enhanced at the same time by the consciousness of her power and dignity.

“Do you know this gentleman?” she asked, with a keen glance.

“Yes, Mother.”

“Go back to your cell, my daughter!” said the Mother imperiously.

The General slipped aside behind the curtain lest the dreadful tumult within him should appear in his face; even in the shadow it seemed to him that he could still see the Superior’s piercing eyes. He was afraid of her; she held his little, frail, hardly-won happiness in her hands; and he, who had never quailed under a triple row of guns, now trembled before this nun. The Duchess went towards the door, but she turned back.

“Mother,” she said, with dreadful calmness, “the Frenchman is one of my brothers.”

“Then stay, my daughter,” said the Superior, after a pause.

The piece of admirable Jesuitry told of such love and regret, that a man less strongly constituted might have broken down under the keen delight in the midst of a great and, for him, an entirely novel peril. Oh! how precious words, looks, and gestures became when love must baffle lynx eyes and tiger’s claws! Sister Theresa came back.

“You see, my brother, what I have dared to do only to speak to you for a moment of your salvation and of the prayers that my soul puts up for your soul daily. I am committing mortal sin. I have told a lie. How many days of penance must expiate that lie! But I shall endure it for your sake. My brother, you do not know what happiness it is to love in heaven; to feel that you can confess love purified by religion, love transported into the highest heights of all, so that we are permitted to lose sight of all but the soul. If the doctrine and the spirit of the Saint to whom we owe this refuge had not raised me above earth’s anguish, and caught me up and set me, far indeed beneath the Sphere wherein she dwells, yet truly above this world, I should not have seen you again. But now I can see you, and hear your voice, and remain calm——”

The General broke in, “But, Antoinette, let me see you, you whom I love passionately, desperately, as you could have wished me to love you.”

“Do not call me Antoinette, I implore you. Memories of the past hurt me. You must see no one here but Sister Theresa, a creature who trusts in the Divine mercy.” She paused for a little, and then added, “You must control yourself, my brother. Our Mother would separate us without pity if there is any worldly passion in your face, or if you allow the tears to fall from your eyes.”

The General bowed his head to regain self-control; when he looked up again he saw her face beyond the grating—the thin, white, but still impassioned face of the nun. All the magic charm of youth that once bloomed there, all the fair contrast of velvet whiteness and the colour of the Bengal rose, had given place to a burning glow, as of a porcelain jar with a faint light shining through it. The wonderful hair in which she took such pride had been shaven; there was a bandage round her forehead and about her face. An ascetic life had left dark traces about the eyes, which still sometimes shot out fevered glances; their ordinary calm expression was but a veil. In a few words, she was but the ghost of her former self.

“Ah! you that have come to be my life, you must come out of this tomb! You were mine; you had no right to give yourself, even to God. Did you not promise me to give up all at the least command from me? You may perhaps think me worthy of that promise now when you hear what I have done for you. I have sought you all through the world. You have been in my thoughts at every moment for five years; my life has been given to you. My friends, very powerful friends, as you know, have helped with all their might to search every convent in France, Italy, Spain, Sicily, and America. Love burned more brightly for every vain search. Again and again I made long journeys with a false hope; I have wasted my life and the heaviest throbbings of my heart in vain under many a dark convent wall. I am not speaking of a faithfulness that knows no bounds, for what is it?—nothing compared with the infinite longings of my love. If your remorse long ago was sincere, you ought not to hesitate to follow me today.”

“You forget that I am not free.”

“The Duke is dead,” he answered quickly.

Sister Theresa flushed red.

“May heaven be open to him!” she cried with a quick rush of feeling. “He was generous to me.—But I did not mean such ties; it was one of my sins that I was ready to break them all without scruple—for you.”

“Are you speaking of your vows?” the General asked, frowning. “I did not think that anything weighed heavier with your heart than love. But do not think twice of it, Antoinette; the Holy Father himself shall absolve you of your oath. I will surely go to Rome, I will entreat all the powers of earth; if God could come down from heaven, I would——”

“Do not blaspheme.”

“So do not fear the anger of God. Ah! I would far rather hear that you would leave your prison for me; that this very night you would let yourself down into a boat at the foot of the cliffs. And we would go away to be happy somewhere at the world’s end, I know not where. And with me at your side, you should come back to life and health under the wings of love.”

“You must not talk like this,” said Sister Theresa; “you do not know what you are to me now. I love you far better than I ever loved you before. Every day I pray for you; I see you with other eyes. Armand, if you but knew the happiness of giving yourself up, without shame, to a pure friendship which God watches over! You do not know what joy it is to me to pray for heaven’s blessing on you. I never pray for myself: God will do with me according to His will; but, at the price of my soul, I wish I could be sure that you are happy here on earth, and that you will be happy hereafter throughout all ages. My eternal life is all that trouble has left me to offer up to you. I am old now with weeping; I am neither young nor fair; and in any case, you could not respect the nun who became a wife; no love, not even motherhood, could give me absolution.... What can you say to outweigh the uncounted thoughts that have gathered in my heart during the past five years, thoughts that have changed, and worn, and blighted it? I ought to have given a heart less sorrowful to God.”

“What can I say? Dear Antoinette, I will say this, that I love you; that affection, love, a great love, the joy of living in another heart that is ours, utterly and wholly ours, is so rare a thing and so hard to find, that I doubted you, and put you to sharp proof; but now, today, I love you, Antoinette, with all my soul’s strength.... If you will follow me into solitude, I will hear no voice but yours, I will see no other face.”

“Hush, Armand! You are shortening the little time that we may be together here on earth.”

“Antoinette, will you come with me?”

“I am never away from you. My life is in your heart, not through the selfish ties of earthly happiness, or vanity, or enjoyment; pale and withered as I am, I live here for you, in the breast of God. As God is just, you shall be happy——”

“Words, words all of it! Pale and withered? How if I want you? How if I cannot be happy without you? Do you still think of nothing but duty with your lover before you? Is he never to come first and above all things else in your heart? In time past you put social success, yourself, heaven knows what, before him; now it is God, it is the welfare of my soul! In Sister Theresa I find the Duchess over again, ignorant of the happiness of love, insensible as ever, beneath the semblance of sensibility. You do not love me; you have never loved me——”

“Oh, my brother——!”

“You do not wish to leave this tomb. You love my soul, do you say? Very well, through you it will be lost forever. I shall make away with myself——”

“Mother!” Sister Theresa called aloud in Spanish, “I have lied to you; this man is my lover!”

The curtain fell at once. The General, in his stupor, scarcely heard the doors within as they clanged.

“Ah! she loves me still!” he cried, understanding all the sublimity of that cry of hers. “She loves me still. She must be carried off....”

The General left the island, returned to headquarters, pleaded ill-health, asked for leave of absence, and forthwith took his departure for France.

And now for the incidents which brought the two personages in this Scene into their present relation to each other.

The thing known in France as the Faubourg Saint-Germain is neither a Quarter, nor a sect, nor an institution, nor anything else that admits of a precise definition. There are great houses in the Place Royale, the Faubourg Saint-Honore, and the Chaussee d’Antin, in any one of which you may breathe the same atmosphere of Faubourg Saint-Germain. So, to begin with, the whole Faubourg is not within the Faubourg. There are men and women born far enough away from its influences who respond to them and take their place in the circle; and again there are others, born within its limits, who may yet be driven forth forever. For the last forty years the manners, and customs, and speech, in a word, the tradition of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, has been to Paris what the Court used to be in other times; it is what the Hotel Saint-Paul was to the fourteenth century; the Louvre to the fifteenth; the Palais, the Hotel Rambouillet, and the Place Royale to the sixteenth; and lastly, as Versailles was to the seventeenth and the eighteenth.

Just as the ordinary workaday Paris will always centre about some point; so, through all periods of history, the Paris of the nobles and the upper classes converges towards some particular spot. It is a periodically recurrent phenomenon which presents ample matter for reflection to those who are fain to observe or describe the various social zones; and possibly an enquiry into the causes that bring about this centralization may do more than merely justify the probability of this episode; it may be of service to serious interests which some day will be more deeply rooted in the commonwealth, unless, indeed, experience is as meaningless for political parties as it is for youth.

In every age the great nobles, and the rich who always ape the great nobles, build their houses as far as possible from crowded streets. When the Duc d’Uzes built his splendid hotel in the Rue Montmartre in the reign of Louis XIV, and set the fountain at his gates—for which beneficent action, to say nothing of his other virtues, he was held in such veneration that the whole quarter turned out in a body to follow his funeral—when the Duke, I say, chose this site for his house, he did so because that part of Paris was almost deserted in those days. But when the fortifications were pulled down, and the market gardens beyond the line of the boulevards began to fill with houses, then the d’Uzes family left their fine mansion, and in our time it was occupied by a banker. Later still, the noblesse began to find themselves out of their element among shopkeepers, left the Place Royale and the centre of Paris for good, and crossed the river to breathe freely in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where palaces were reared already about the great hotel built by Louis XIV for the Duc de Maine—the Benjamin among his legitimated offspring. And indeed, for people accustomed to a stately life, can there be more unseemly surroundings than the bustle, the mud, the street cries, the bad smells, and narrow thoroughfares of a populous quarter? The very habits of life in a mercantile or manufacturing district are completely at variance with the lives of nobles. The shopkeeper and artisan are just going to bed when the great world is thinking of dinner; and the noisy stir of life begins among the former when the latter have gone to rest. Their day’s calculations never coincide; the one class represents the expenditure, the other the receipts. Consequently their manners and customs are diametrically opposed.

Nothing contemptuous is intended by this statement. An aristocracy is in a manner the intellect of the social system, as the middle classes and the proletariat may be said to be its organizing and working power. It naturally follows that these forces are differently situated; and of their antagonism there is bred a seeming antipathy produced by the performance of different functions, all of them, however, existing for one common end.

Such social dissonances are so inevitably the outcome of any charter of the constitution, that however much a Liberal may be disposed to complain of them, as of treason against those sublime ideas with which the ambitious plebeian is apt to cover his designs, he would none the less think it a preposterous notion that M. le Prince de Montmorency, for instance, should continue to live in the Rue Saint-Martin at the corner of the street which bears that nobleman’s name; or that M. le Duc de Fitz-James, descendant of the royal house of Scotland, should have his hotel at the angle of the Rue Marie Stuart and the Rue Montorgueil. Sint ut sunt, aut non sint, the grand words of the Jesuit, might be taken as a motto by the great in all countries. These social differences are patent in all ages; the fact is always accepted by the people; its “reasons of state” are self-evident; it is at once cause and effect, a principle and a law. The common sense of the masses never deserts them until demagogues stir them up to gain ends of their own; that common sense is based on the verities of social order; and the social order is the same everywhere, in Moscow as in London, in Geneva as in Calcutta. Given a certain number of families of unequal fortune in any given space, you will see an aristocracy forming under your eyes; there will be the patricians, the upper classes, and yet other ranks below them. Equality may be a right, but no power on earth can convert it into fact. It would be a good thing for France if this idea could be popularized. The benefits of political harmony are obvious to the least intelligent classes. Harmony is, as it were, the poetry of order, and order is a matter of vital importance to the working population. And what is order, reduced to its simplest expression, but the agreement of things among themselves—unity, in short? Architecture, music, and poetry, everything in France, and in France more than in any other country, is based upon this principle; it is written upon the very foundations of her clear accurate language, and a language must always be the most infallible index of national character. In the same way you may note that the French popular airs are those most calculated to strike the imagination, the best-modulated melodies are taken over by the people; clearness of thought, the intellectual simplicity of an idea attracts them; they like the incisive sayings that hold the greatest number of ideas. France is the one country in the world where a little phrase may bring about a great revolution. Whenever the masses have risen, it has been to bring men, affairs, and principles into agreement. No nation has a clearer conception of that idea of unity which should permeate the life of an aristocracy; possibly no other nation has so intelligent a comprehension of a political necessity; history will never find her behind the time. France has been led astray many a time, but she is deluded, woman-like, by generous ideas, by a glow of enthusiasm which at first outstrips sober reason.

So, to begin with, the most striking characteristic of the Faubourg is the splendour of its great mansions, its great gardens, and a surrounding quiet in keeping with princely revenues drawn from great estates. And what is this distance set between a class and a whole metropolis but visible and outward expression of the widely different attitude of mind which must inevitably keep them apart? The position of the head is well defined in every organism. If by any chance a nation allows its head to fall at its feet, it is pretty sure sooner or later to discover that this is a suicidal measure; and since nations have no desire to perish, they set to work at once to grow a new head. If they lack the strength for this, they perish as Rome perished, and Venice, and so many other states.

This distinction between the upper and lower spheres of social activity, emphasized by differences in their manner of living, necessarily implies that in the highest aristocracy there is real worth and some distinguishing merit. In any state, no matter what form of “government” is affected, so soon as the patrician class fails to maintain that complete superiority which is the condition of its existence, it ceases to be a force, and is pulled down at once by the populace. The people always wish to see money, power, and initiative in their leaders, hands, hearts, and heads; they must be the spokesmen, they must represent the intelligence and the glory of the nation. Nations, like women, love strength in those who rule them; they cannot give love without respect; they refuse utterly to obey those of whom they do not stand in awe. An aristocracy fallen into contempt is a roi faineant, a husband in petticoats; first it ceases to be itself, and then it ceases to be.

And in this way the isolation of the great, the sharply marked distinction in their manner of life, or in a word, the general custom of the patrician caste is at once the sign of a real power, and their destruction so soon as that power is lost. The Faubourg Saint-Germain failed to recognise the conditions of its being, while it would still have been easy to perpetuate its existence, and therefore was brought low for a time. The Faubourg should have looked the facts fairly in the face, as the English aristocracy did before them; they should have seen that every institution has its climacteric periods, when words lose their old meanings, and ideas reappear in a new guise, and the whole conditions of politics wear a changed aspect, while the underlying realities undergo no essential alteration.

These ideas demand further development which form an essential part of this episode; they are given here both as a succinct statement of the causes, and an explanation of the things which happen in the course of the story.

The stateliness of the castles and palaces where nobles dwell; the luxury of the details; the constantly maintained sumptuousness of the furniture; the “atmosphere” in which the fortunate owner of landed estates (a rich man before he was born) lives and moves easily and without friction; the habit of mind which never descends to calculate the petty workaday gains of existence; the leisure; the higher education attainable at a much earlier age; and lastly, the aristocratic tradition that makes of him a social force, for which his opponents, by dint of study and a strong will and tenacity of vocation, are scarcely a match-all these things should contribute to form a lofty spirit in a man, possessed of such privileges from his youth up; they should stamp his character with that high self-respect, of which the least consequence is a nobleness of heart in harmony with the noble name that he bears. And in some few families all this is realised. There are noble characters here and there in the Faubourg, but they are marked exceptions to a general rule of egoism which has been the ruin of this world within a world. The privileges above enumerated are the birthright of the French noblesse, as of every patrician efflorescence ever formed on the surface of a nation; and will continue to be theirs so long as their existence is based upon real estate, or money; domaine-sol and domaine-argent alike, the only solid bases of an organized society; but such privileges are held upon the understanding that the patricians must continue to justify their existence. There is a sort of moral fief held on a tenure of service rendered to the sovereign, and here in France the people are undoubtedly the sovereigns nowadays. The times are changed, and so are the weapons. The knight-banneret of old wore a coat of chain armor and a hauberk; he could handle a lance well and display his pennon, and no more was required of him; today he is bound to give proof of his intelligence. A stout heart was enough in the days of old; in our days he is required to have a capacious brain-pan. Skill and knowledge and capital—these three points mark out a social triangle on which the scutcheon of power is blazoned; our modern aristocracy must take its stand on these.

A fine theorem is as good as a great name. The Rothschilds, the Fuggers of the nineteenth century, are princes de facto. A great artist is in reality an oligarch; he represents a whole century, and almost always he is a law to others. And the art of words, the high pressure machinery of the writer, the poet’s genius, the merchant’s steady endurance, the strong will of the statesman who concentrates a thousand dazzling qualities in himself, the general’s sword—all these victories, in short, which a single individual will win, that he may tower above the rest of the world, the patrician class is now bound to win and keep exclusively. They must head the new forces as they once headed the material forces; how should they keep the position unless they are worthy of it? How, unless they are the soul and brain of a nation, shall they set its hands moving? How lead a people without the power of command? And what is the marshal’s baton without the innate power of the captain in the man who wields it? The Faubourg Saint-Germain took to playing with batons, and fancied that all the power was in its hands. It inverted the terms of the proposition which called it into existence. And instead of flinging away the insignia which offended the people, and quietly grasping the power, it allowed the bourgeoisie to seize the authority, clung with fatal obstinacy to its shadow, and over and over again forgot the laws which a minority must observe if it would live. When an aristocracy is scarce a thousandth part of the body social, it is bound today, as of old, to multiply its points of action, so as to counterbalance the weight of the masses in a great crisis. And in our days those means of action must be living forces, and not historical memories.

In France, unluckily, the noblesse were still so puffed up with the notion of their vanished power, that it was difficult to contend against a kind of innate presumption in themselves. Perhaps this is a national defect. The Frenchman is less given than anyone else to undervalue himself; it comes natural to him to go from his degree to the one above it; and while it is a rare thing for him to pity the unfortunates over whose heads he rises, he always groans in spirit to see so many fortunate people above him. He is very far from heartless, but too often he prefers to listen to his intellect. The national instinct which brings the Frenchman to the front, the vanity that wastes his substance, is as much a dominant passion as thrift in the Dutch. For three centuries it swayed the noblesse, who, in this respect, were certainly pre-eminently French. The scion of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, beholding his material superiority, was fully persuaded of his intellectual superiority. And everything contributed to confirm him in his belief; for ever since the Faubourg Saint-Germain existed at all—which is to say, ever since Versailles ceased to be the royal residence—the Faubourg, with some few gaps in continuity, was always backed up by the central power, which in France seldom fails to support that side. Thence its downfall in 1830.

At that time the party of the Faubourg Saint-Germain was rather like an army without a base of operation. It had utterly failed to take advantage of the peace to plant itself in the heart of the nation. It sinned for want of learning its lesson, and through an utter incapability of regarding its interests as a whole. A future certainty was sacrificed to a doubtful present gain. This blunder in policy may perhaps be attributed to the following cause.

The class-isolation so strenuously kept up by the noblesse brought about fatal results during the last forty years; even caste-patriotism was extinguished by it, and rivalry fostered among themselves. When the French noblesse of other times were rich and powerful, the nobles (gentilhommes) could choose their chiefs and obey them in the hour of danger. As their power diminished, they grew less amenable to discipline; and as in the last days of the Byzantine Empire, everyone wished to be emperor. They mistook their uniform weakness for uniform strength.

Each family ruined by the Revolution and the abolition of the law of primogeniture thought only of itself, and not at all of the great family of the noblesse. It seemed to them that as each individual grew rich, the party as a whole would gain in strength. And herein lay their mistake. Money, likewise, is only the outward and visible sign of power. All these families were made up of persons who preserved a high tradition of courtesy, of true graciousness of life, of refined speech, with a family pride, and a squeamish sense of noblesse oblige which suited well with the kind of life they led; a life wholly filled with occupations which become contemptible so soon as they cease to be accessories and take the chief place in existence. There was a certain intrinsic merit in all these people, but the merit was on the surface, and none of them were worth their face-value.

Not a single one among those families had courage to ask itself the question, “Are we strong enough for the responsibility of power?” They were cast on the top, like the lawyers of 1830; and instead of taking the patron’s place, like a great man, the Faubourg Saint-Germain showed itself greedy as an upstart. The most intelligent nation in the world perceived clearly that the restored nobles were organizing everything for their own particular benefit. From that day the noblesse was doomed. The Faubourg Saint-Germain tried to be an aristocracy when it could only be an oligarchy—two very different systems, as any man may see for himself if he gives an intelligent perusal to the list of the patronymics of the House of Peers.

The King’s Government certainly meant well; but the maxim that the people must be made to will everything, even their own welfare, was pretty constantly forgotten, nor did they bear in mind that La France is a woman and capricious, and must be happy or chastised at her own good pleasure. If there had been many dukes like the Duc de Laval, whose modesty made him worthy of the name he bore, the elder branch would have been as securely seated on the throne as the House of Hanover at this day.

In 1814 the noblesse of France were called upon to assert their superiority over the most aristocratic bourgeoisie in the most feminine of all countries, to take the lead in the most highly educated epoch the world had yet seen. And this was even more notably the case in 1820. The Faubourg Saint-Germain might very easily have led and amused the middle classes in days when people’s heads were turned with distinctions, and art and science were all the rage. But the narrow-minded leaders of a time of great intellectual progress all of them detested art and science. They had not even the wit to present religion in attractive colours, though they needed its support. While Lamartine, Lamennais, Montalembert, and other writers were putting new life and elevation into men’s ideas of religion, and gilding it with poetry, these bunglers in the Government chose to make the harshness of their creed felt all over the country. Never was nation in a more tractable humour; La France, like a tired woman, was ready to agree to anything; never was mismanagement so clumsy; and La France, like a woman, would have forgiven wrongs more easily than bungling.

If the noblesse meant to reinstate themselves, the better to found a strong oligarchy, they should have honestly and diligently searched their Houses for men of the stamp that Napoleon used; they should have turned themselves inside out to see if peradventure there was a Constitutionalist Richelieu lurking in the entrails of the Faubourg; and if that genius was not forthcoming from among them, they should have set out to find him, even in the fireless garret where he might happen to be perishing of cold; they should have assimilated him, as the English House of Lords continually assimilates aristocrats made by chance; and finally ordered him to be ruthless, to lop away the old wood, and cut the tree down to the living shoots. But, in the first place, the great system of English Toryism was far too large for narrow minds; the importation required time, and in France a tardy success is no better than a fiasco. So far, moreover, from adopting a policy of redemption, and looking for new forces where God puts them, these petty great folk took a dislike to any capacity that did not issue from their midst; and, lastly, instead of growing young again, the Faubourg Saint-Germain grew positively older.

Etiquette, not an institution of primary necessity, might have been maintained if it had appeared only on state occasions, but as it was, there was a daily wrangle over precedence; it ceased to be a matter of art or court ceremonial, it became a question of power. And if from the outset the Crown lacked an adviser equal to so great a crisis, the aristocracy was still more lacking in a sense of its wider interests, an instinct which might have supplied the deficiency. They stood nice about M. de Talleyrand’s marriage, when M. de Talleyrand was the one man among them with the steel-encompassed brains that can forge a new political system and begin a new career of glory for a nation. The Faubourg scoffed at a minister if he was not gently born, and produced no one of gentle birth that was fit to be a minister. There were plenty of nobles fitted to serve their country by raising the dignity of justices of the peace, by improving the land, by opening out roads and canals, and taking an active and leading part as country gentlemen; but these had sold their estates to gamble on the Stock Exchange. Again the Faubourg might have absorbed the energetic men among the bourgeoisie, and opened their ranks to the ambition which was undermining authority; they preferred instead to fight, and to fight unarmed, for of all that they once possessed there was nothing left but tradition. For their misfortune there was just precisely enough of their former wealth left them as a class to keep up their bitter pride. They were content with their past. Not one of them seriously thought of bidding the son of the house take up arms from the pile of weapons which the nineteenth century flings down in the market-place. Young men, shut out from office, were dancing at Madame’s balls, while they should have been doing the work done under the Republic and the Empire by young, conscientious, harmlessly employed energies. It was their place to carry out at Paris the programme which their seniors should have been following in the country. The heads of houses might have won back recognition of their titles by unremitting attention to local interests, by falling in with the spirit of the age, by recasting their order to suit the taste of the times.

But, pent up together in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where the spirit of the ancient court and traditions of bygone feuds between the nobles and the Crown still lingered on, the aristocracy was not whole-hearted in its allegiance to the Tuileries, and so much the more easily defeated because it was concentrated in the Chamber of Peers, and badly organized even there. If the noblesse had woven themselves into a network over the country, they could have held their own; but cooped up in their Faubourg, with their backs against the Chateau, or spread at full length over the Budget, a single blow cut the thread of a fast-expiring life, and a petty, smug-faced lawyer came forward with the axe. In spite of M. Royer-Collard’s admirable discourse, the hereditary peerage and law of entail fell before the lampoons of a man who made it a boast that he had adroitly argued some few heads out of the executioner’s clutches, and now forsooth must clumsily proceed to the slaying of old institutions.

There are examples and lessons for the future in all this. For if there were not still a future before the French aristocracy, there would be no need to do more than find a suitable sarcophagus; it were something pitilessly cruel to burn the dead body of it with fire of Tophet. But though the surgeon’s scalpel is ruthless, it sometimes gives back life to a dying man; and the Faubourg Saint-Germain may wax more powerful under persecution than in its day of triumph, if it but chooses to organize itself under a leader.

And now it is easy to give a summary of this semi-political survey. The wish to re-establish a large fortune was uppermost in everyone’s mind; a lack of broad views, and a mass of small defects, a real need of religion as a political factor, combined with a thirst for pleasure which damaged the cause of religion and necessitated a good deal of hypocrisy; a certain attitude of protest on the part of loftier and clearer-sighted men who set their faces against Court jealousies; and the disaffection of the provincial families, who often came of purer descent than the nobles of the Court which alienated them from itself—all these things combined to bring about a most discordant state of things in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. It was neither compact in its organisation, nor consequent in its action; neither completely moral, nor frankly dissolute; it did not corrupt, nor was it corrupted; it would neither wholly abandon the disputed points which damaged its cause, nor yet adopt the policy that might have saved it. In short, however effete individuals might be, the party as a whole was none the less armed with all the great principles which lie at the roots of national existence. What was there in the Faubourg that it should perish in its strength?

It was very hard to please in the choice of candidates; the Faubourg had good taste, it was scornfully fastidious, yet there was nothing very glorious nor chivalrous truly about its fall.

In the Emigration of 1789 there were some traces of a loftier feeling; but in the Emigration of 1830 from Paris into the country there was nothing discernible but self-interest. A few famous men of letters, a few oratorical triumphs in the Chambers, M. de Talleyrand’s attitude in the Congress, the taking of Algiers, and not a few names that found their way from the battlefield into the pages of history—all these things were so many examples set before the French noblesse to show that it was still open to them to take their part in the national existence, and to win recognition of their claims, if, indeed, they could condescend thus far. In every living organism the work of bringing the whole into harmony within itself is always going on. If a man is indolent, the indolence shows itself in everything that he does; and, in the same manner, the general spirit of a class is pretty plainly manifested in the face it turns on the world, and the soul informs the body.

The women of the Restoration displayed neither the proud disregard of public opinion shown by the court ladies of olden time in their wantonness, nor yet the simple grandeur of the tardy virtues by which they expiated their sins and shed so bright a glory about their names. There was nothing either very frivolous or very serious about the woman of the Restoration. She was hypocritical as a rule in her passion, and compounded, so to speak, with its pleasures. Some few families led the domestic life of the Duchesse d’Orleans, whose connubial couch was exhibited so absurdly to visitors at the Palais Royal. Two or three kept up the traditions of the Regency, filling cleverer women with something like disgust. The great lady of the new school exercised no influence at all over the manners of the time; and yet she might have done much. She might, at worst, have presented as dignified a spectacle as English-women of the same rank. But she hesitated feebly among old precedents, became a bigot by force of circumstances, and allowed nothing of herself to appear, not even her better qualities.

Not one among the Frenchwomen of that day had the ability to create a salon whither leaders of fashion might come to take lessons in taste and elegance. Their voices, which once laid down the law to literature, that living expression of a time, now counted absolutely for nought. Now when a literature lacks a general system, it fails to shape a body for itself, and dies out with its period.

When in a nation at any time there is a people apart thus constituted, the historian is pretty certain to find some representative figure, some central personage who embodies the qualities and the defects of the whole party to which he belongs; there is Coligny, for instance, among the Huguenots, the Coadjuteur in the time of the Fronde, the Marechal de Richelieu under Louis XV, Danton during the Terror. It is in the nature of things that the man should be identified with the company in which history finds him. How is it possible to lead a party without conforming to its ideas? or to shine in any epoch unless a man represents the ideas of his time? The wise and prudent head of a party is continually obliged to bow to the prejudices and follies of its rear; and this is the cause of actions for which he is afterwards criticised by this or that historian sitting at a safer distance from terrific popular explosions, coolly judging the passion and ferment without which the great struggles of the world could not be carried on at all. And if this is true of the Historical Comedy of the Centuries, it is equally true in a more restricted sphere in the detached scenes of the national drama known as the Manners of the Age.

At the beginning of that ephemeral life led by the Faubourg Saint-Germain under the Restoration, to which, if there is any truth in the above reflections, they failed to give stability, the most perfect type of the aristocratic caste in its weakness and strength, its greatness and littleness, might have been found for a brief space in a young married woman who belonged to it. This was a woman artificially educated, but in reality ignorant; a woman whose instincts and feelings were lofty while the thought which should have controlled them was wanting. She squandered the wealth of her nature in obedience to social conventions; she was ready to brave society, yet she hesitated till her scruples degenerated into artifice. With more wilfulness than real force of character, impressionable rather than enthusiastic, gifted with more brain than heart; she was supremely a woman, supremely a coquette, and above all things a Parisienne, loving a brilliant life and gaiety, reflecting never, or too late; imprudent to the verge of poetry, and humble in the depths of her heart, in spite of her charming insolence. Like some straight-growing reed, she made a show of independence; yet, like the reed, she was ready to bend to a strong hand. She talked much of religion, and had it not at heart, though she was prepared to find in it a solution of her life. How explain a creature so complex? Capable of heroism, yet sinking unconsciously from heroic heights to utter a spiteful word; young and sweet-natured, not so much old at heart as aged by the maxims of those about her; versed in a selfish philosophy in which she was all unpractised, she had all the vices of a courtier, all the nobleness of developing womanhood. She trusted nothing and no one, yet there were times when she quitted her sceptical attitude for a submissive credulity.